Beyond the Grave: The Victorians, a study in morbidity

This article was originally written for Sainte Magazine.

The Victorians were kind of obsessed with the macabre, but they probably didn’t realize it.

SPIRITUALISM

Their straight-laced (very tempting to insert a joke about corsets, but I won’t… ) set of morals and the deeply emotional and dramatic nature of communing with the dead are two things that, on the surface, absolutely do not go together. But, in truth, communicating with the dead and the practice of Spiritualism thrived in 19th Century North America and England.

The strict following of traditional religion had begun to ebb with the crest of scientific research and discovery (it was also this time that Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species, presenting his theories on evolution). This is not to say that people were no longer religious or that religion, namely Christianity, did not play a role in every facet of Victorian life -- it was still the kind of God-fearing culture of shame, bigotry, and restriction that might be considered a modern conservative’s wet dream. But people began to shy away from taking it so literally, and this frightening new world of industry and science allowed for the masses to embrace ideas that had previously been considered fantastic.

Seances, not too different from what we might imagine today, allowed members of the upper and middle classes to bring Spiritualism into their homes through more than books and magazines, and were taken seriously enough that even world leaders could not resist. First Lady Jane Pierce, wife of President Franklin Pierce, invited mediums Margaret and Kate Fox into The White House to commune with her dead son. Many credit the Fox sisters with having started the Spiritualism craze in the United States when they claimed to have communicated with the spirit of a man who’d been murdered in their house before their family moved in. Years later, Mary Todd Lincoln held several seances in The White House, at least one of which her husband, President Abraham Lincoln, attended. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert participated in the practice as early as 1846, and continued to do so throughout the remainder of their lives.

RITUALS AND SUPERSTITIONS

It was the ability to come face-to-face with the spirits of the dead (or, their representatives) that, naturally, seems to have led to heightening their respect for death and dying and, in turn, modifying and intensifying their mourning and burial practices.

Victorian mourning was morbid, but decorative. Wearing jewelry made of the deceased’s hair, most frequently fashioned into an ornate locket or brooch, was a common means of literally keeping that person with you forever.

Due to the belief that the spirit of the dead could get trapped in mirrors and beckon the remaining family members to the afterlife with them, people in mourning took to covering every mirror in the house with black fabric.

Similarly, Victorians believed that if a body was carried out of the home head first, its spirit could look back into the house and call for another to join them. So, just to be safe, the corpse was always carried out feet first.

“Give Pop Pop your hair…” a mourning brooch, adorned with the deceased’s hair

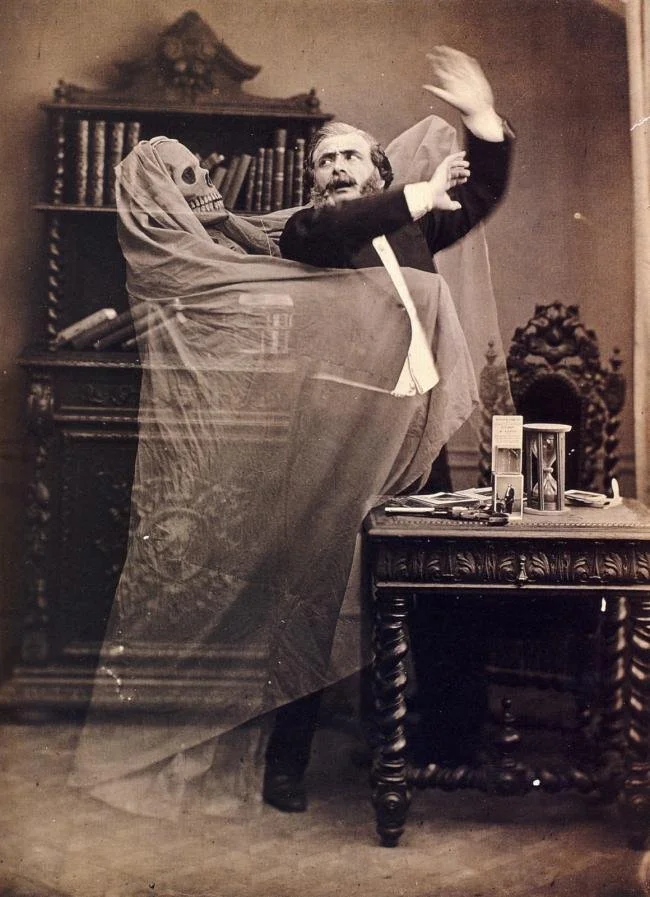

The burgeoning art of photography found a home in the macabre as well. “Spirit photography” used double exposures to create the effect of a spirit lingering in the background of a scene, often in the presence of one or several of their still-living family members. Mourners often took photographs with their deceased loved ones, too. As portraits were incredibly expensive and most families could not afford to get them taken willy-nilly, the event of one of them dying would push them to scrounge up whatever money they could for one last chance at a photo together.

Grave robbers, known as “Resurrection Men”, took to robbing graves of their corpses in order to sell them to medical schools -- the fresher the better. To avoid this, the extremely wealthy invested in individual or family mausoleums, with the casket entombed within the mausoleum or sealed into a crypt in the wall.

Widows had to observe three distinct stages of mourning before they could respectably “move on”. The first stage, “deep mourning”, called for the widow to wear a black dress and veil for a year and a day following her husband’s death. During “second mourning”, she could remove her veil but had to primarily wear black. This lasted for around nine months, sometimes as long as a year. “Half mourning”, the last stage, allowed the widow to wear colored clothing with black accents, but certainly nothing too bright, extravagant or gaudy. Of course, some people were in mourning for the rest of their lives following the death of a loved one. When her beloved husband, Prince Albert, died suddenly from typhoid at the age of 42, Queen Victoria wore black every day until her own death four decades later.

Although some of these practices seem a little much to me (hard pass on wearing someone’s hair) and some are downright foolish (forcing someone to mourn a certain way and for a certain length of time for the sake of respectability is despicable), death is a completely incomprehensible thing. Like everything else, it’s all a matter of perspective. Maybe the death portraits seem a little Weekend at Bernie’s to you, but what do we know? We carry our cameras in our pockets and take photos of anything we want.

Likewise, floating tables, disembodied voices, and possessed mediums might seem like cliche devices in horror films and Scooby-Doo cartoons, but they were far more precious than that to Victorians. All they wanted was a chance for one last moment with someone they loved, an instance for closure, an opportunity for one last goodbye.

You can never know how losing someone will affect you, and I can’t help but appreciate the fervor with which the Victorians did everything they could to keep the connection between the living and the dead… alive.